By Roselyn Romero, Vincent Torres

For two weeks, Cammie Velci did not know how her son had died.

Emilio Velci, 19, had been experiencing some wisdom tooth pain, and over-the-counter medications weren’t helping. After bringing up the issue at work, one coworker offered him a Percocet, a combination medication of oxycodone and acetaminophen that is used to treat moderate to severe pain. Emilio turned it down, hoping to deal with the pain on his own.

But the discomfort became unbearable, making it harder for him to fall asleep at night. Eventually, he followed up on his coworker’s offer: he reached out on Snapchat and purchased three Percocet pills, one of which he would take on the night of March 8, 2020.

Emilio went home to his father’s house in Atascadero for the weekend, played with his siblings and then retired to his room for the evening. There, he took the pill and relaxed in the comfort of his room where he played video games into the night.

On the morning of March 9, 2020, Cammie’s phone rang.

“For some reason, in my heart and in my gut, I just knew,” Cammie said.

It was her ex-husband. Emilio was dead.

Autopsy reports showed Emilio died of fentanyl poisoning, something that had never crossed Cammie’s mind. She said she wasn’t even sure what fentanyl was at the time.

“I started calling my other sons and I said, ‘Your brother was using heroin,’ and they were like, ‘What are you talking about? Nobody’s ever done heroin,’” Cammie said.

Cammie’s reaction to the cause of Emilio’s death shows that fentanyl is a fairly new addition to the drug scene — it wasn’t until 2013 that fentanyl-related deaths have skyrocketed in the U.S., according to a March 2017 congressional hearing discussing the drug overdose epidemic.

But one of the most overlooked aspects of the fentanyl crisis is how social media plays a role in how teens and young adults obtain their drugs.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid up to 50 times stronger than heroin and up to 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Common brands of fentanyl include Duragesic, Abstral, Subsys and Ionsys. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is cheap to produce, making it easier for clandestine labs to create in mass quantities.

But fentanyl, which can come in liquid and powder forms, is often mixed with other drugs or can be produced to look like other drugs, deceiving those who expected to take another substance.

In Emilio’s case, the pill that he thought was a Percocet was actually made of pure fentanyl.

“One pill can kill, and it killed my son,” Cammie said.

The Atascadero resident’s death reflects a rapidly evolving drug overdose epidemic disproportionately hitting teenagers and young adults across the country. Nearly 104,000 Americans died of drug overdose in 2021, according to preliminary data reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of those deaths, almost 66% were due to synthetic opioids, which includes fentanyl.

Data of the opioid crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic paints an even gloomier picture: Fatal drug overdoses increased 30% in 2020 compared to 2019, with most state and local health departments pointing to illicitly manufactured fentanyl as the most common cause of death, data from the CDC shows.

This staggering trend is also reflected locally — fentanyl was the biggest killer among drug overdoses in 2020 in San Luis Obispo County, according to data from the San Luis Obispo County Sheriff-Coroner’s Office.

In the same year, five people under age 25 died of an overdose in San Luis Obispo County. In 2021, 11 people under 25 died of an overdose. They all had fentanyl in their system.

Of the 11, one was under 5 years old and six were between 15 and 19 years old.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, drug overdoses have steadily risen along California’s Central Coast. In 2016, San Luis Obispo County recorded a total of 43 overdose deaths. The following two years, the county recorded similar yearly totals.

In 2019, however, San Luis Obispo county recorded a slightly higher total: 53 people had died of an overdose.

In 2020, that number shot up by about 66% — 88 county residents died of an overdose that year. Of those deaths, 34 people had fentanyl in their system, more than triple the count in 2019.

The San Luis Obispo County Public Health Department forwarded Mustang News drug overdose data from January 2021 to Sept. 5, 2021. An analysis of that data reflects the trend: in the first nine months in 2021, the 84 total overdose deaths are only four shy away from the total count in 2020.

Furthermore, the county recorded 48 fentanyl-related overdose deaths in just about nine months in 2021. That’s approximately 41% higher than the 34 fentanyl-related overdose deaths in 2020.

County health experts told Mustang News the sale of illicitly manufactured fentanyl — and the subsequent surge in fentanyl-related overdose deaths — is expected to reach record levels in 2022.

Drug busts involving fentanyl have already sprouted in San Luis Obispo County. One of the most recent drug seizures took place in Nipomo in April: during a traffic stop, deputies with the San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Office found a kilogram, or about 2.2 pounds, of fentanyl inside a person’s vehicle.

How Snapchat plays into the problem

Atascadero resident Mariah Byler, who was close friends with Emilio since elementary school, said Snapchat is one of the most convenient venues for drug sales as sellers and customers can make their profiles anonymous.

“No one communicates that stuff over text,” Byler said. “Everyone does it through a social media platform since it’s accessible to everyone.”

Plus, Snap Inc. Terms of Service states that the minimum age requirement for Snapchat users is 13, further reducing barriers for youth to obtain illicitly manufactured drugs.

There are two types of messages that can be sent on the app: snaps and chats. Snaps are photos or videos that expire as soon as a user opens it. Similarly, chats are deleted automatically once they are read.

For both messages, users have the option to replay the snap or keep the chat, but it is not the default.

If someone were to screenshot a user’s chat or snap, the user would be automatically notified of the screenshot, making it harder for people to collect proof of drug deals.

For many drug sales on Snapchat, an interested customer simply needs to know the username of the drug seller. From there, the customer can add the seller as their friend.

Once the seller approves the customer’s friend request, the customer can view the seller’s “story,” which is a collection of photos or videos that a Snapchat user posts over the past 24 hours. After 24 hours, the user’s story is automatically deleted.

Drug dealers can advertise their products stealthily by only permitting certain users to view their story. This means the seller can handpick their customers from their friends list, prohibiting others from watching their “private” story.

On these private stories, a drug dealer can post their “menu,” a list of all the substances they are selling and the price of each item. Like other advertisements, the menus may also offer deals and discounts or highlight their most popular products, further incentivizing customers to make a purchase.

To further avoid detection, drug sellers can also use emojis on their menus to represent certain substances rather than naming the drug. For example, a snowman or snowflake emoji may symbolize cocaine and a school bus emoji may stand for Xanax, according to Cammie.

Once the transaction is complete, the drug seller can drive to the customer’s house and drop off the product or meet the customer for pickup. The man who sold the fentanyl pill to Emilio delivered it to the 19-year-old at his place of work at night, Cammie said, so no one in the house could have known about the sale.

Snapchat has partnered with Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America and Truth Initiative, two nonprofits that aim to spread awareness of the dangers of substance misuse.

“We will continue to build on this critical work, with additional partnerships and operational improvements underway,” Snap Inc. stated in a news release.

How law enforcement and other local agencies are responding

The San Luis Obispo County District Attorney’s Office has been working with local law enforcement and community members to crack down on criminal and civil cases involving the illegal sale and possession of fentanyl, including Emilio’s case.

In May 2020, the office announced in a news release that it had charged 22-year-old Timothy Clark Wolfe of Paso Robles with second-degree murder in connection to Emilio’s death. Prosecutors also accused Wolfe of selling fentanyl and possessing Xanax and promethazine for sale, all of which are felonies, according to a complaint filed by the District Attorney’s Office.

Prosecutors did not accuse Wolfe of manufacturing the counterfeit drugs.

“We will not tolerate the criminal distribution of heroin, fentanyl, and other hard drugs because too many young people have been dying across our country and here in our community,” San Luis Obispo County District Attorney Dan Dow stated in the release.

In the complaint, prosecutors allege that Wolfe knew or should have known the pills contained fentanyl and “were extremely dangerous to human life” at the time he sold them to Emilio.

Court documents show Wolfe pleaded not guilty to all three charges at his arraignment hearing at the San Luis Obispo County Superior Court in May 2020. The Paso Robles resident is scheduled to appear in court again on Aug. 1.

The San Luis Obispo County District Attorney’s Office Bureau of Investigation, Atascadero Police Department and Paso Robles Police Department investigated Emilio’s case.

Working alongside Dow, San Luis Obispo County Deputy District Attorney Eric Dobroth has been tasked with developing the office’s policies and procedures in response to local drug overdose cases.

In the cases they have observed, both Dow and Dobroth said they noticed social media played a major role in how community members obtained substances containing illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

“We’re hearing from law enforcement that Snapchat is one of the most prevalent ways people are obtaining it,” Dobroth said. “It’s a good platform for getting customers.”

To facilitate the investigation into these digital platforms, the San Luis Obispo County District Attorney’s Office partnered with Cal Poly’s California Cybersecurity Institute, the California Attorney General’s Office, the U.S. Department of Justice and community law enforcement to establish the Central Coast Cyber Forensic Lab (3CFL) in 2017.

The lab provides access to digital forensic evidence collection platforms to all law enforcement agencies in San Luis Obispo County, including the Cal Poly Police Department, according to the 3CFL website.

“Law enforcement is definitely using every tool that we have to mine information and gather evidence electronically to see where this stuff is happening,” Dow said.

The District Attorney’s Office isn’t alone in the fight against the opioid crisis in the county. The San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Office, the San Luis Obispo City Fire Department and the San Luis Obispo Police Department have also launched awareness campaigns to educate community members of the risks of illicitly manufactured opioids.

Another group working on the frontlines of the opioid crisis is the SLO County Opioid Safety Coalition, which the San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health Department started in January 2016 as a response to the growing overdose epidemic.

Funded by the non-profit California Health Care Foundation, the coalition is comprised of physicians, law enforcement, pharmacists, treatment professionals, educators and other community members dedicated to drug overdose prevention.

In January, the coalition collaborated with Cal Poly’s Digital Transformation Hub (DxHub) to launch Naloxone Now, a web-based app for San Luis Obispo County residents with drug overdose resources.

The app, which was created with the help of Amazon Web Services, outlines the signs of an overdose and provides instructions on how to administer naloxone, or NARCAN, a nasal spray or injectable medication that blocks the body’s receptors that react to opioids and restores a person’s breathing.

Cal Poly biological sciences professor Dr. Candace Winstead, who is involved in the Opioid Safety Coalition, said everyone should learn how to administer NARCAN.

“It’s just like carrying an EpiPen,” Winstead said. “The more people who carry naloxone and know how to recognize and respond to an overdose, the more they’re going to save lives and destigmatize it.”

Though Cal Poly has exhausted its NARCAN supply for the 2021-2022 academic year, campus and community members can request a free delivery of naloxone to their home through the Naloxone Now app.

Winstead also volunteers for SLO Bangers, a harm reduction program that offers syringe exchanges, provides overdose response training and hosts pop-ups throughout the county where community members can pick up a free overdose prevention kit. The weekly schedule for those pop-ups can be found here.

Qualifying entities can also request NARCAN through the California Department of Health Care Services’ Naloxone Distribution Project. Since October 2018, the project has issued more than 1 million units of naloxone and recorded more than 57,000 overdose reversals.

Moving forward

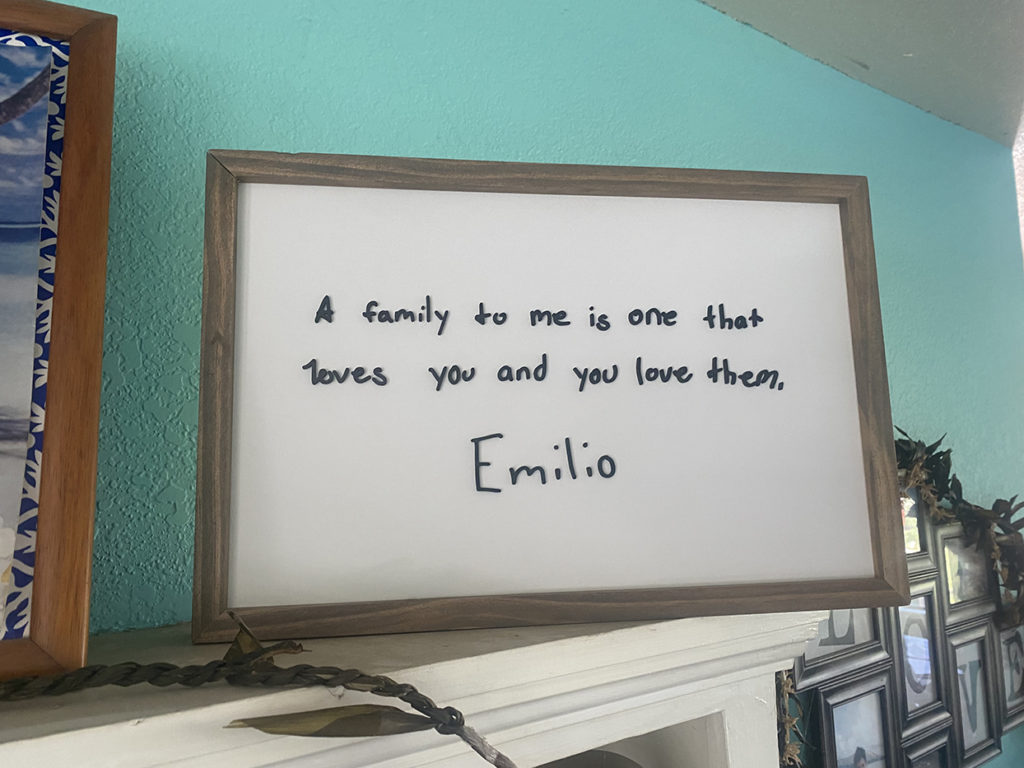

Cammie honors her son’s memory through the Emilio Velci Share Aloha Project, a non-profit foundation she launched with the goal of creating fentanyl awareness campaigns through education and advocacy.

The Emilio Velci Share Aloha Project offered scholarships this year to six high school seniors: three student athletes at Atascadero High School and another three at Paloma Creek High School in Atascadero.

The scholarship application consisted of a 500-word essay in which students had to answer the question, “What does ‘aloha’ mean to you and how can you live it in your life?”

Cammie said she wanted to give back to the community because Emilio gave back while he was alive, coaching and refereeing for youth basketball games at the Atascadero Recreation Center.

“‘Aloha’ means so many things, but it truly means compassion and generosity and love, and Emilio embodied the spirit of aloha tremendously,” Cammie said. “He had the biggest heart.”

Featured Image by Cammie Velci | Courtesy